Practical Introduction to Mapping with Stata

This is a relatively short, practical introduction to mapping with Stata designed to get the newcomer started in no time and provide a quick refresher as needed.

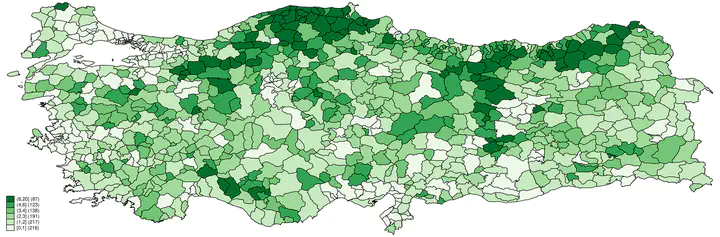

In this tutorial1, we will draw a choropleth map (assigning various colors to levels of a variable to show intensity) of mosque density in Turkey at the district level.2 In this first step of spatial analysis, we need two separate things: A map with the required boundaries marking the units we are interested in, and substantive data corresponding to the geographical units marked by the borders in the map. The map files are freely available on the internet, and the one we will use can be obtained from Shapefiles. We will need the turkey_administrativelevels0_1_2.zip file. This zip file contains the administrative boundaries for the country, provinces, and districts. In this tutorial, we are creating a map at the district level and this is the second level. After unzipping the file, extract the following files to a folder of your choice:3

- tur_polbnda_adm2.cpg

- tur_polbnda_adm2.dbf

- tur_polbnda_adm2.prj

- tur_polbnda_adm2.sbn

- tur_polbnda_adm2.sbx

- tur_polbnda_adm2.shp

- tur_polbnda_adm2.shp.xml

- tur_polbnda_adm2.shx

Now that we have our shapefile in folder, we will need to generate / get our substantive data for the variable that we want to map.4For this tutorial, grab the substantive dataset and place it in the same folder as with the shapefiles.5

Before we get down to it, two words of advice: First, it is important to realize these types of detailed maps do not show causation per se (Healy 2018, 182).6 Second, I intentionally did not provide a .do file so that the reader will type the commands themselves, and generate their own .do files with the comments that they think will be useful in the future. This - I have been led to believe - is a best practice in learning.

Let us start typing those commands!

1. Preliminaries

First order of business, as usual, is to check where in the file system we are. Using the following command, check the current working directory and point Stata to the folder of our files by Shift+Control+F.

pwd

Now that we are where we want to be in the file system, we will use Stata’s built-in spatial commands. First, issue the following command to have Stata use all the shapefiles in our folder to generate a .dta dataset that we can manipulate using Stata.

spshape2dta tur_polbnda_adm2, replace

We will see the following output on the console, confirming that Stata used all the shapefiles to create a .dta file that we can manipulate.

use "tur_polbnda_adm2.dta", clear

describe

encode pcode, generate(dcode)

drop pcode

rename dcode pcode

sort pcode

gen id = _n

Let us check our work.

describe

save "tur_polbnda_adm2.dta", replace

Just like we define a time-series dataset to Stata using the “tsset” command, while our dataset is in memory, we define it as a spatial dataset with the following command:

spset

In order to check if this definition is successful, we use Stata’s built-in grmap command to see if Stata can draw the borders in this dataset. This is the spatial dataset and will include only the borders.

grmap

spset, modify coordsys(latlong, kilometers)

Our preliminary work is done. We prepared our map dataset to be used in the analysis. Now we need to merge the datasets in such a way that the new dataset will now not only have borders (spatial information) but also values of our variable of interest (here mosque density) corresponding to each of those units. So, it will be possible to create a choropleth map. We save our dataset before proceeding.

save "tur_polbnda_adm2.dta", replace

2. Merging Datasets

Let us load our substantive dataset of this tutorial and have a look at it.

use "abus_mosque_density.dta", clear

describe

A look at the first few lines of the dataset show that each district has an id variable starting from 1 and the counting starts from the very first district of the first province (pcode starts from “TUR001001”). This is the way I prepared this substantive dataset and I suggest using two unique identifiers7 for each observation as a best practice.

use "tur_polbnda_adm2.dta", clear

Then we load our master dataset (substantial dataset).

use "abus_mosque_density.dta", clear

The second dataset we load in this workflow is our main dataset. The code below allows us to merge the datasets. In effect, we are adding spatial data to our dataset. We are using our two unique identifiers. This means those observations that are uniquely identified in both datasets become one observation and additional information is added to that observation (here spatial data).

merge 1:1 pcode id using "tur_polbnda_adm2.dta"

drop _merge

3. The Map!

Now we have a dataset that is “spset” and includes the spatial information of the variable of interest (mosque density). It is now a matter of issuing a grmap command with the variable to be mapped (here mosquedens). grmap has alot of options that can be checked by

help grmap

Below, we are using 7 intervals and through the custom option we define the breaking points for these intervals. We are using the Greens color scheme from Brewer and we are including the count as a legend (but without an explanatory text).

grmap mosquedens, clnumber(7) clmethod(custom) ///

clbreaks(0 1 2 3 4 6 20) fcolor(Greens) legcount

We can save our map as a regular Stata .gph file, which is 🆒.

save "mosquedensity.gph", replace

We can export it to a number of formats.

graph export "mosquedensity.pdf", replace

graph export "mosquedensity.svg", replace

Thanks for reading!8

-

This fast tutorial was inspired by Cameron Wimpy. ↩︎

-

For a more detailed and formal introduction, please see the multi-part series of Asjad Naqvi. ↩︎

-

Note that for this particular case, the .zip file included files ending with “0”, “1”, and “2”. These correspond to the administrative units of the country. Files with “0” would be used to draw the country borders, files with “1” would be used to draw the province borders and here we are using the files with “2” to draw the district borders. By the same logic, there are separate shapefiles containing information about the railways, waterways, roads, etc. ↩︎

-

This tutorial assumes that the files be placed in a single folder. Beyond that there is no assumption about any particular folder-subfolder structure choice. ↩︎

-

Note that I compiled this dataset to reflect mosque density for each of 973 administrative districts in Turkey. ↩︎

-

Healy, Kieran. 2018. Data Visualization: A Practical Introduction. Princeton University Press. ↩︎

-

Unique identifiers are also referred to as keys. ↩︎

-

Screenshots are from Stata IC 16.1 running on a Linux machine (Ubuntu 22.04 / GNOME 42.1) ↩︎